Journalism in the Age of Slopaganda

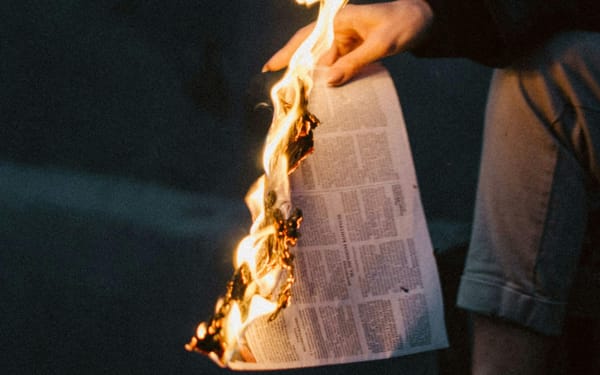

How does one stem the tide of disinformation?

When many of us think of "propaganda," our minds drift to the iconic posters of WWI and WWII. Films of goose-stepping Nazis meant to project overwhelming power. Posters of confident (white) Americans encouraging the public to buy war bonds. Strong Soviet figures guiding the world to a better future.

Propaganda hasn't looked like that in a long time, but it has marched on ever since. The introduction of generative AI has supercharged the ability for everyday people to create imagery that reflects the reality they believe in, and then push that view onto wider society. In February, Gareth Watkins' essay in the New Socialist on how AI-generated art maps perfectly onto far-right ideology provided compelling analysis. In a thorough piece that links the interests of Silicon Valley corporations with AI's widespread use, Watkins pinpoints a key reason that it has taken off in far-right circles. "The right wing aesthetic project is to flood the zone with bullshit in order to erode the intellectual foundations for resisting political cruelty." AI, then, provides the tools and the mass-production of propaganda that fulfills that end.

And so, the bullshit flowed. AI-generated propaganda has become a serious problem in an already dismal media literacy landscape. Political talking points and disasters have been muddied with fake images. Unreliable studies are using image generation to illustrate their flawed points, spewed out thanks to multi-billion dollar tech companies desperate for a profitable use case. All created and spread in mere minutes. Most of this deluge is accepted, if not encouraged, by the platforms they're shared on. Slop on slop on slop.

I'm not the first person to use the term "slopaganda" but it's clear this new iteration of the age-old political communication is different. Traditional propaganda, in the manner we currently understand it, was meant to affirm the beliefs of the public. It was created to foster the belief that its opinion or viewpoint was popularly held. Those who disagreed were not necessarily meant to be convinced. If they did, that was good news, but its primary aim was to intimidate and pressure dissenters into compliance. Slopaganda, aided with the ease of generative AI tools, then becomes a supercharged feedback loop.

Whether it's a self-assured small social media account, an established online conservative activist or, indeed, a department of the US government, the viewing public isn't the only target of this new form of propaganda. In this manner, the creator also experiences the same reassurance from interactions online. Truth is not the goal, the goal is affirmation of both the audience and the creator that, yes, their beliefs are tangible.

Canada has been faced with this phenomenon in concerning ways. Prior to the federal election, fake AI-generated images of Prime Minister Mark Carney went viral. Recently, CBC News investigated a TikTok account presenting videos of a young white man named "Josh" who was having difficulty finding work, blaming Indian immigrants for his unemployment. In this case, the account was run by AI firm Nexa. When asked about the clear racism on display in the TikTok videos, Nexa CEO Divy Nayyar said he wanted to "have fun" with the racist idea that "Indians are taking over the job market." Sounds like a blast.

Meanwhile, a YouTube channel that's reached third most watched Canada-based news and politics in the past three months has reached those heights by "content farming." In one case mentioned in the article, this was being assisted with AI voiceover. One video posted to the channel, Ronald Reagan tells a joke with AI voiceover. The person behind the channel said they found it on YouTube and just posted it, unaware it was AI. Whether this is actually what happened is beside the point, ignorance is at the heart of all slopaganda.

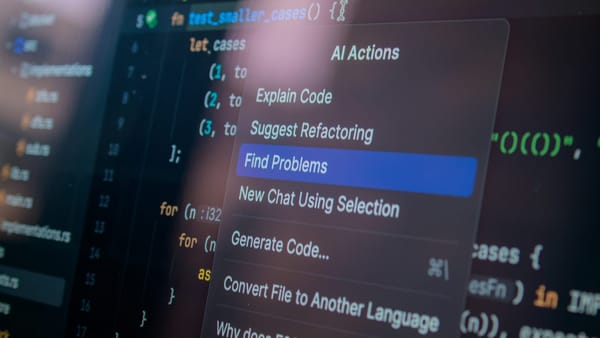

This is an uncontrolled deluge of mass-produced disinformation created by slopagandists. No tech firm seems interested in stopping it. Indeed, companies like Meta are integrating their AI tech into their business model. Advertising and engagement are being supercharged in the company with the use of AI. Considering those two are fundamental pillars that bring Meta money, why should they stop?

Meanwhile, Grok, Elon Musk's vanity AI project, recently went on a tirade spouting Nazi talking points, calling itself "MechaHitler." Though disgusting, it's certainly more efficient. Cut out the middle man. Why have far-right actors use AI to affirm their propaganda when you can get the AI itself to spew it?

When reading the CBC investigation into the TikTok AI personality, and when following stories of AI spam accounts reported on by journalists, it's become clear that this is a beat that will continue into the future. But in essence, this is merely delegating moderation duties of these platforms onto third-parties. Journalists find AI accounts or ads spreading something harmful, and these platforms take action after they're reached for comment. In one case of an advertiser on Meta claiming they would donate to both Kamala Harris and Donald Trump for purchases of their shirt, the game became clear: "After 404 Media reached out to Meta for comment, hundreds of ads were deleted from the platform."

While these are important areas of coverage, the dereliction of duty by these platforms has become normalized. Platforms shouldn't outsource their moderation to journalists looking to expose problems. They should be held accountable for the destructive slopaganda they facilitate, which is having real-world effects. Pleasant though this thought may be, there is no sign this is coming any time soon, especially under the Carney government. So journalism, already in a precarious position, is now, apparently, the only institution tasked with covering misinformation.

The conservative infosphere, right-wing political entities and big tech companies are all benefiting from this phenomenon. Meanwhile, solutions are sparse. Telling individuals to "be skeptical of what you see online," for example, is not any way to solve this problem. Journalists need to understand the effects of AI on disinformation as a cohesive whole. Instead of framing the purveyors as one-off instances, there needs to be a comprehensive way of reporting on the AI sector's role in political polarization and disinformation. Even though this is important, it should be clear that there is no internal way for the news industry to tackle this issue. It's not a news issue. It's a slopaganda issue... and it's a society-wide problem. One that our government is not interested in tackling.