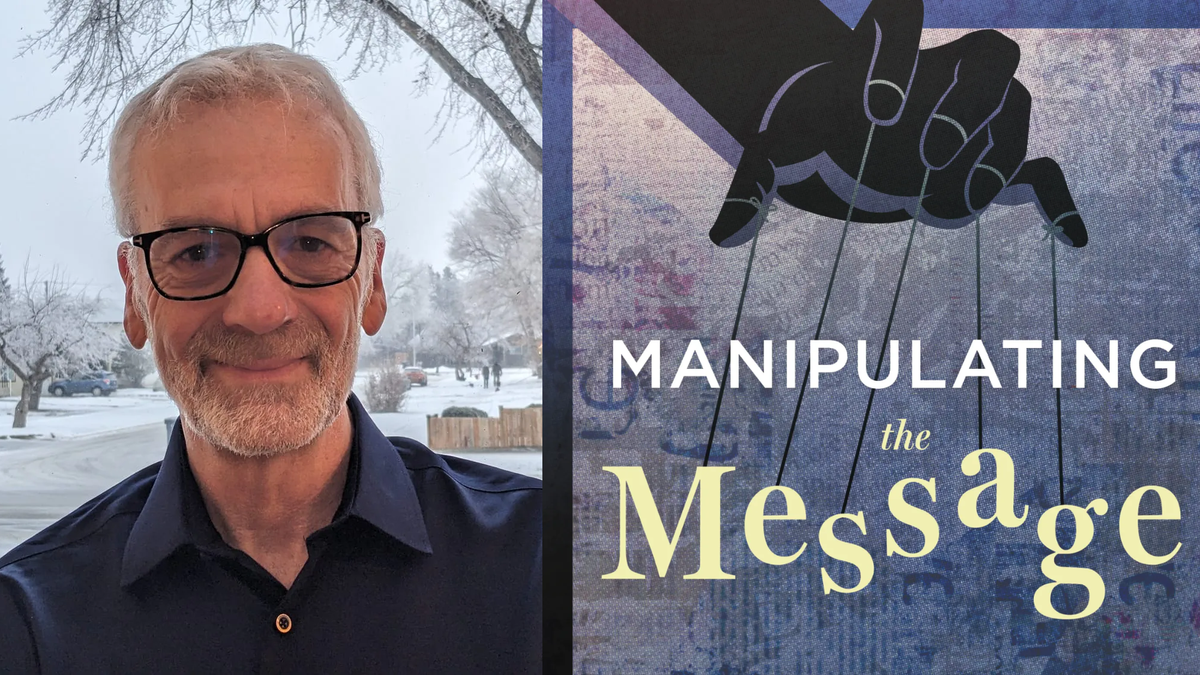

'I've seen with my own eyes how journalists sometimes don't bother to unpack,' Cecil Rosner on News Manipulation

Rosner talked about how the book came about, valuable lessons journalists can take from it and the future of journalism in a bleak time.

Cecil Rosner, veteran reporter, adjunct professor at the University of Winnipeg and managing editor at the Investigative Journalism Foundation knows a few things about journalism. He managed CBC Manitoba for 15 years, was an executive producer on The Fifth Estate and produced investigative reporting that covered issues across Canada. One notable event included Conservative Prime Minister Brian Mulroney's finance minister, Michael Wilson, leaving important documents on a desk after a press conference in 1984. Rosner was the journalist who took the opportunity to go through those documents in order to fact-check some of Wilson's claims.

Needless to say, Rosner has first-hand experience in the field. That's why his latest book Manipulating the Message: How Powerful Forces Shape the News, released in October 2023, hits as hard as it does. The book examines the many different ways that journalists can be duped into reporting information coloured by the very sources they use for the story, specifically in the Canadian context. I reached out to him for an interview about Manipulating the Message and the current state of journalism. Rosner talked about how the book came about, valuable lessons journalists can take from it and why he's still hopeful about the future of journalism in a bleak time.

The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You've had a long career spanning more than 40 years in journalism. So what was the impetus to write this book when you did?

I have written some books before. It's a big job, sort of time consuming. My prior books I wrote while I was still working. I had left the CBC and so I had the time, to be honest. It's sort of a combination of things that I was ruminating about and then I thought, 'Well, I've seen a lot of these things in practice in my career.' It's not just an academic book, where I'm musing about different things. I felt I had specific examples of things that I could use to illustrate that. The other factor is there's all this talk swirling around these days about misinformation and disinformation, as if it's something new, as if this just started because some Russian bots started pumping out material in 2016. I wanted to point out that no, it's not new. It's been going on forever.

So how long was it in your head that this is a project that you wanted to pursue? Maybe you thought of it and you didn't have the time?

I do a fair bit of teaching, which allows me to think about issues in journalism. In my days at the CBC, on three or four occasions, I was called upon to set up a reality check unit, or a disinformation busting unit. The last time I did that was when COVID started. So in 2020, we created a unit at the CBC that I was in charge of, to look at all the theories and disinformation, which a lot of it was, coming out about the pandemic. I've done that in the past. When the Gulf War broke out, with the US invasion and Saddam Hussein, we set up a reality check unit. Especially in times of war, that's when a lot of misinformation and disinformation really ramps up. So these kinds of topics have always been on my mind and I thought it's important for journalists to know about these things. Too often, working journalists don't give themselves enough time to think broadly about these things. They're just so busy doing their job, getting that next story out, that they get swept up in things and they get duped a lot of the time. So I just wanted to put my thoughts down on paper.

A lot of times in the book, you mention that journalists are crushed with a deadline or don't have the resources and time. Can you expand a little bit more on that in the current context? I did find it in the book, but it didn't receive as much focus as maybe some other things.

One of the things I enjoyed in doing this book was researching the history of public relations, which actually hadn't done in any in any significant way before. It's fascinating. I go into it somewhat in the book, the earliest practitioners of public public relations were totally unabashed in declaring that they're here to create propaganda to manipulate public opinion. Edward Bernays, he's held up as one of the great theoreticians of public relations in the United States, his 1928 textbook on this is called Propaganda! A lot of it, though, gets masked. There's all these astroturf organizations that various industries create in order to pull the wool over the eyes of the public. It pulls the wool over the eyes of a lot of journalists too, unfortunately. So I go into some of these examples in the book, whether it's the tobacco industry, or the asbestos industry or the energy industry trying to deny climate change.

For decades, Big Tobacco argued that "No, the science is still not out, there's still doubt," even though the science was totally resolved decades beforehand. The media became an instrument for them in promulgating those ideas. I see a lot of think tanks playing that function now, as well. You have all these think tanks set up in Canada, they're given these generic sounding names like the "Fraser Institute" and "MacDonald Laurier." "Whoa, that must be very credible. It's named after a couple of former prime ministers." They put out a press release, they put out a report and then it just gets repeated uncritically. I have a copy of the Winnipeg Free Press on my table from yesterday. It's talking about increases to MLA wages and quotes "a watchdog" on this. Who's the watchdog? The Canadian Taxpayers Federation. The only people who have decision making power in the Canadian Taxpayers Federation are their handful of board of directors, and yet the media considers that they're somehow a spokesperson for all taxpayers. So this isn't an accident.

A lot of these think tanks and foundations are well funded by large corporations to disseminate messaging that is favourable to those interests. That's what I wanted to point out in the book. I've seen with my own eyes how journalists sometimes don't bother to unpack. "Who is delivering this press release to me? Who is authoring this report? What are the objectives of this? Is there a conflict of interest here? Is this credible?" I think it's a problem and everything that we all know is going on in the world of journalism today with layoffs and shutdowns, it just makes the problem more acute. Reporters have less and less time to delve deeply into some of these things.

So you see it as sort of a systemic problem that existed before this current state, but it's been exacerbated by the latest trends in the industry.

Yeah, it's always been around. I don't want to say that it's something new. It's not something new. It didn't come about because of social media or Twitter or bot farms. Is it worse today than it was? Yeah, I think it is actually, for a whole bunch of reasons. The main one being that there are fewer journalists around and the pressures on reporters are much greater now than they have been in the past. I was in charge of the major newsroom. CBC Manitoba had dozens of employees. I saw with my own eyes. I was an instrument of it. Assigning people to do a story for television and radio and the web. The more platforms you have to feed, and the quicker the deadline, the less time you have to verify facts or even to think critically about different pieces of information. Then you have the impact of social media, which impacts all of us whether we want to admit it or not. It's the constant drumbeat of various types of messages coming at us all. Of course, we know that the more money and resources you have, the more ability you have to manufacture those messages and make sure that they get pushed out. So yeah, I think it's a problem that's been around forever and it's definitely getting worse.

After an introduction, the format of the book, chapter by chapter, evaluates these problems. There's a chapter on the military, a chapter on the police, things like that. This might be a simple answer, but can you explain how this format for the book arose?

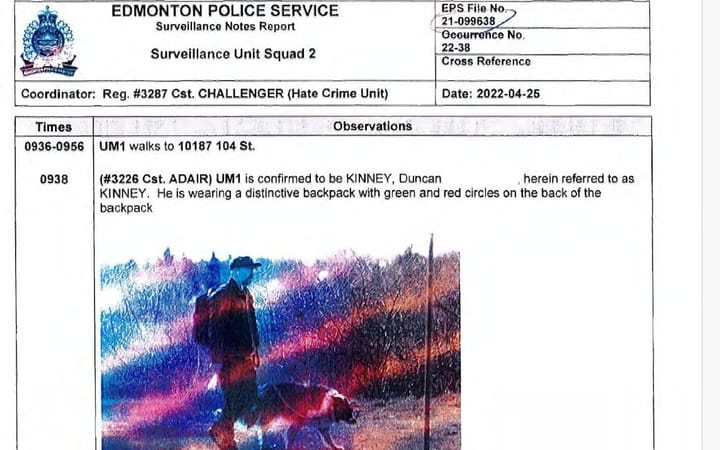

They're all examples that I felt had the same theme, but I felt it was important enough to stress them all in some detail. When you talk about holding powerful interests to account, which is a core value of investigative journalism, it should be a core value of all journalism, then you have to say, well, "Who are those powerful interests?" Well, government clearly is one of them. Large companies and corporations are included there. The police and military hold really special places in society. We vest them with the authority to carry weapons, and arrest people and go to war. So it's important to subject them to scrutiny. That's why I divided the book in that way. Then I got into some themes that I thought were really important to mention, like how science can get distorted. Scientific information can get manipulated, which, especially in the COVID era, we saw in spades. A lot of scientific information people try to manipulate and distort,. Then I also have a chapter on polling, which, again, is another tool used by powerful interests to try to shape public opinion and it's connected to science. It has the aura of scientific validity. Some journalists do probe into the valid scientific approaches and valid polling approaches, but I don't think it's done enough. You start to see how all of that, in my mind, all the chapters, and the way it's divided, are all different illustrations of how messaging gets manipulated.

I do think that's a strength of the book. By focusing on each of these, you see patterns emerge. Can you talk a little bit about how much overlap happens? Because when you're reading it, it's very easy to realize a problem and then move on to the next one. These are all factors facing journalists regularly.

They are. One of the things that was stressed when I was in journalism school is you have to be able to cover any subject at the drop of a hat. There's that old thing "Academics know a lot of information about a small topic area and journalists know a little bit of information about a lot of different subjects." That was presented as a strength of journalists to me. But, actually, I don't think that's a strength at all. I think that's a weakness of journalism– That a journalist might go and tackle a topic that they know nothing about and they're more likely to get misled as a result. I am an advocate of journalists getting informed and educated about the things that they want to tackle. Otherwise, it's very easy to get duped. It's very easy for people to take advantage of you, to use you as a megaphone to disseminate their messaging. So yes, I agree with you, all of these things are connected. But there are different aspects of different situations.

That's why I'm glad to see some smaller news organizations springing up that are specializing in particular things. Take The Narwhal, for instance. They're saying "Our thing is the environment. Our thing is climate change." The people that they work with and hire– That's their beat, that's their area of expertise and they're less likely, in my mind, to get duped, or to get manipulated than a general assignment reporter at a large media outlet might. The PR agencies and the manipulators of information know these things. They deliberately try to take advantage of the fact that journalists are busy and harried and are running around trying to get quotes and clips and file for their deadline. Believe me, the PR agencies, many of which are staffed by former journalists, fully understand how the game is played and they try to use it to their advantage. So that's why I thought it was important to point out. There could have been all kinds of more chapters on different aspects. But you take any type of reporting, whether it's science reporting, or reporting on politics, reporting on polls, or police reporting, and these same features present themselves. Sometimes they present themselves in somewhat different ways, but I think they're all important to understand.

I want to move on to a couple notable things that have happened since the publishing of your book last October. Things we've seen, at least in journalism, have been this military framework, considering the war in Gaza, and the complete butchering of certain journalist outlets, like we've seen with Vice. So in regards to those two things, is there anything that– you publish the book and, immediately after, you go, "I should have included something on that?"

That's the problem with writing a book, it immediately gets ossified in time, right? The book was written before the Gaza situation started. Although, you know, I talked about the New York Times visual investigations work and they did an investigation into Israeli bombings in Gaza, not in 2023, obviously. But look, anytime a conflict like that breaks out or a big international event occurs, you get all the very predictable themes emerging. The Canadian government is allied with Israel. It puts out that messaging. I'm an advocate of trying to figure out what the facts are independent of any messaging that comes from either the direct participants or combatants in any conflict or the allies of those people. That can be a very difficult thing to do because we live in the real world. When it comes to the "Oh that hospital was just bombed, who bombed it?" You have to try to do independent journalism to figure that out. That is not always an easy task. But it's not good enough just to listen to the IDF, or one side or the other, and take their word for it. Everyone is going to spin you their version of events, as they do on every topic.

Even if you look at WWI coverage and WWII coverage, a lot of it was skewed by the propaganda, which I go into. The most famous example, of course, is the whole "We must invade Saddam Hussein because he possesses weapons of mass destruction." The vast majority of mainstream US journalists parroted that thesis, which, as we all know, turned out to be false. As I point out, the pressure on journalists to fall in line with what your own government is saying is actually very palpable. I'll give you an example. It's not of war, but it's a different issue. You remember the incident of the two Michaels? Well, how was that presented by the Canadian government? China has kidnapped these innocent Canadians and is holding them in a form of hostage diplomacy because they didn't like the fact that Canada was detaining Meng Wanzhou in Vancouver. That's how almost every story read. We now know that narrative isn't exactly correct. There's a lot of credible evidence that at least one of the Michaels was engaging in espionage. The Canadian government has now paid a $7 million settlement to the other Michael, who thought "Gee, I was just having friendly chats with that guy, and it seems he was passing along my information." Where were the naysaying, contrarian, free thinking Canadian journalists at the time saying, "Maybe there's another side of the story?" That's what I'm talking about when I'm telling you about critical thinking and critical inquiry. Just because your government is saying something, it doesn't mean that thing is true. Quite often, it will mean that thing isn't true, actually, if we go by experience.

Then the other thing you mentioned, yes, journalism keeps getting cut. Salt Wire just made its announcement. That's why we can't leave journalism in the hands of hedge funds, or market forces, for that matter. It's not working. Like the PostMedia chain is now reduced to a shambles of what it once was. The objective of the US hedge fund is not to produce good journalism, it's to create profit and profits for its shareholders. Which is why we need a different models other than leaving the future of journalism to the market, in my opinion.

On that note of different models, I remember I spoke briefly to you about the cooperative model, the startups. Is that enough? What more can be done to bolster journalism?

To be honest, I don't know enough of the ins and outs of those models. I know CHEK TV in BC is operating on that model right now. I do know that there's been two or three instances where media outlets have been saved from going under and bankruptcy by converting into a cooperative model. So from that point of view, it's good. Is it enough? Probably not. It's probably a good step. But I think other things have to happen. This is where government has a role to play, a role that has to be protected.

I worked at the CBC for a long time, and the CBC is largely government financed, but it doesn't mean the CBC is a state broadcaster. It doesn't get memos from cabinet saying, "Please cover this story." That's not the way the CBC works. I think there's things CBC can do to maintain even greater independence from government that it probably should do. But I think the CBC model shows that you can have government support for journalism, and still maintain independent journalism. I was involved in lots of stories at the CBC that severely embarrassed governments in power at the time. I was at The Fifth Estate in 2020-2021. We did stories about WE charity. Huge embarrassment to the Trudeau government. All of which to say is that I think the government needs to support journalism in different ways. Encourage the hiring of reporters, give tax breaks to startups that want to delve deeply into different aspects of Canadian society. As long as the mechanisms are in place to maintain editorial independence. But I think that's possible.

In the book, you have a chapter dedicated to politicians. It seems we're at a time now in the milieu where you have the Conservatives saying "Defund the CBC" and, I think there was recently an initiative to bolster more funding, but Trudeau hasn't necessarily stepped up in places. Ads are still an increasing chunk of CBC. So how do we, as a society make sure this happens?

It's hard. In English Canada, especially, it's hard, because, as you know, we're overwhelmed by the US culture. CBC is one of like, I don't know how many dozens and dozens of television stations, all competing for the same audience. CBC Radio has a much more distinctive voice and there's not as much kind of competition in the news and current affairs space. Then in Quebec, SRC has much more public support, because there's such a distinct voice with very few competitive alternatives. I don't know, that's a good question. CBC often gets criticized by all parties. Public broadcasting, I think is a valuable asset to any country. It needs to be supported. It needs to be guarded against political interference, but it's important. As I said earlier: What's the alternative? We can't leave journalism to big corporations. 30- 40 years ago big corporations knew how to make money out of journalism. It's becoming less and less clear that they can figure out how to do that anymore, and their answer is, "Let's just cut it." But that doesn't serve our democracy. Canadians need to know things. Were at a pretty critical juncture right now, when some big decisions have to be made about how journalism survives.

This might be a sad question. But you mentioned the "Weapons of Mass Destruction" in the early 2000s. The Intercept has done good work delving into claims the New York Times has done recently. So my question is, how often are we in the industry going to have to write this book?

I don't know. All I can do is put it out there. I don't know how many people will actually consume it. But look, there are big structural things that always happen in any society, and even though all the forces may seem like it's determining an outcome of something, I think there's a role of individual journalists to make a difference no matter where they are. I really do. If you work in Russia, right now, the pressure on you as a journalist might be intense to support Vladimir Putin. There are courageous people that will try to write the truth about things no matter where they live, and that includes Canada. I give an example in the book of Seymour Hersh. Here's a guy who uncovered war crimes being committed by US forces in Vietnam, and no mainstream American publication was willing to print that. But he succeeded in getting it into print, anyway. You might sit back and say, "Oh, well, the forces of the establishment are so powerful in the US that they drown out all the other voices." Well, yeah, but here's the voice that succeeded in not getting drowned out.

That's why I'm still hopeful. I'm hopeful that more journalists will come out of journalism school and say, "I'm going to ask the critical questions, even though maybe my colleagues around me aren't. I'm going to fight all these conventional narratives that I see and I'm going to try to get to the truth of things. I'm not just going to be satisfied with what someone has given me in a press release, or what some think tank has produced in a report." So I think every generation produces people like that, and they can make a huge difference. Maybe they'll write some similar books in the future. But along the way, I think they'll do some good work, too.

Comments ()